Curated by Kristen Coy, Kaylee Nok & Iris Mang

Opening March 8th, 2023

The Virtual Commons @ The Barney Building

Artists

“Open House: Object-making as a Therapeutic Practice” highlights the ways in which art can function as a form of translation. Art has the ability to transform feelings into something tangible, something that others can interact with and connect to, even without the presence of words. The artists in this exhibition have an interest in the practice of repetition. Through the act of repeating an action, artists Susan Behrends Valenzuela, Rachel Graves, Victoria Sherwood, Paloma Brites and Briana Pierre are engaging in personal meditative practices. Through repeating certain actions: crocheting, weaving, applying paint to a surface and glass blowing, these artists are able to relieve stress and work through difficult, often multi-layered feelings. In addition to their modes of creation, the artists are connected through themes of intimacy, vulnerability and art as a form of release.

Art-making and artistic practice have an immense capacity for healing. Sometimes, words cannot fully articulate feelings, but a creative action can help release and relieve tension. Artistic expression can be cathartic; it can function as a therapeutic tool for coping with trauma. Works of art can unite viewers, artists and entire communities through emotional expression and shared experiences of vulnerability.

Susan Behrends Valenzuela’s practice involves intimate aspects of her personal life. Often taking inspiration from old family photographs––both digitally: her mother’s Facebook uploads, and physically: childhood photo albums, these photos invite feelings of nostalgia. Susan developed an interest in exploring album photographs through her own artistic production, perhaps in an effort to take control of the narrative––she is now “behind the camera” instead of in front of it. Susan began archiving family photos, feeling especially connected to photos of and taken by female family members. These images and her connection to them influenced Susan’s practice moving forward. As a result, memory manifests itself in her works; Behrends Valenzuela re-contextualizes memories through her own creative freedom, describing them from her own personal perspective.

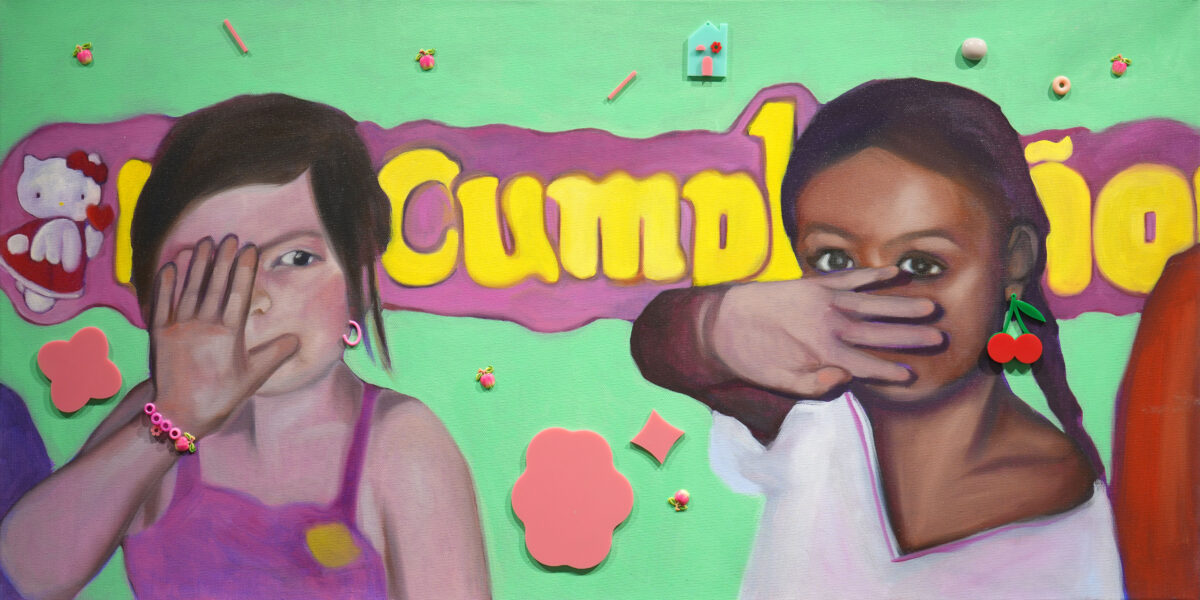

Also drawing from personal and digital archives, Briana Pierre facilitates conversations between spirits. Forms emerge from surreal backdrops of color, creating ghosts on the canvas, each containing their own story. Pierre uses the canvas to exercise the relationships between these ghosts—between human and animal, family members, and from woman to woman. It is through the layering of medium, texture, images, and color that she becomes a storyteller. The resulting collage of material mirrors the intersectionality of her subjects, who are connected by both their similarities and their differences. Pierre leaves many of her compositions unfinished—allowing for viewer’s imaginations to generate endless narratives.

Like both Susan Behrends Valenzuela and Briana Pierre, Rachel Graves explores themes of shared human experiences and emotional connection. In her series of portraits of young adults in New York City, she portrays simple and stylized human forms to reveal the essence of her community. In her saturated colors and extravagant forms, she captures a youthful group that embraces creativity, individuality, and activism. As a child and adolescent mental studies minor, Graves grew a profound interest in learning about art therapy and its positive effects on personal growth. She approaches art as a therapeutic practice. By painting intuitively without sketching, she focuses on genuine expression and finds release from preconceived expectations on the artist’s role in society. Her figures, embodying her own pursuit for authenticity, confront the audience with a striking sense of honesty and energy.

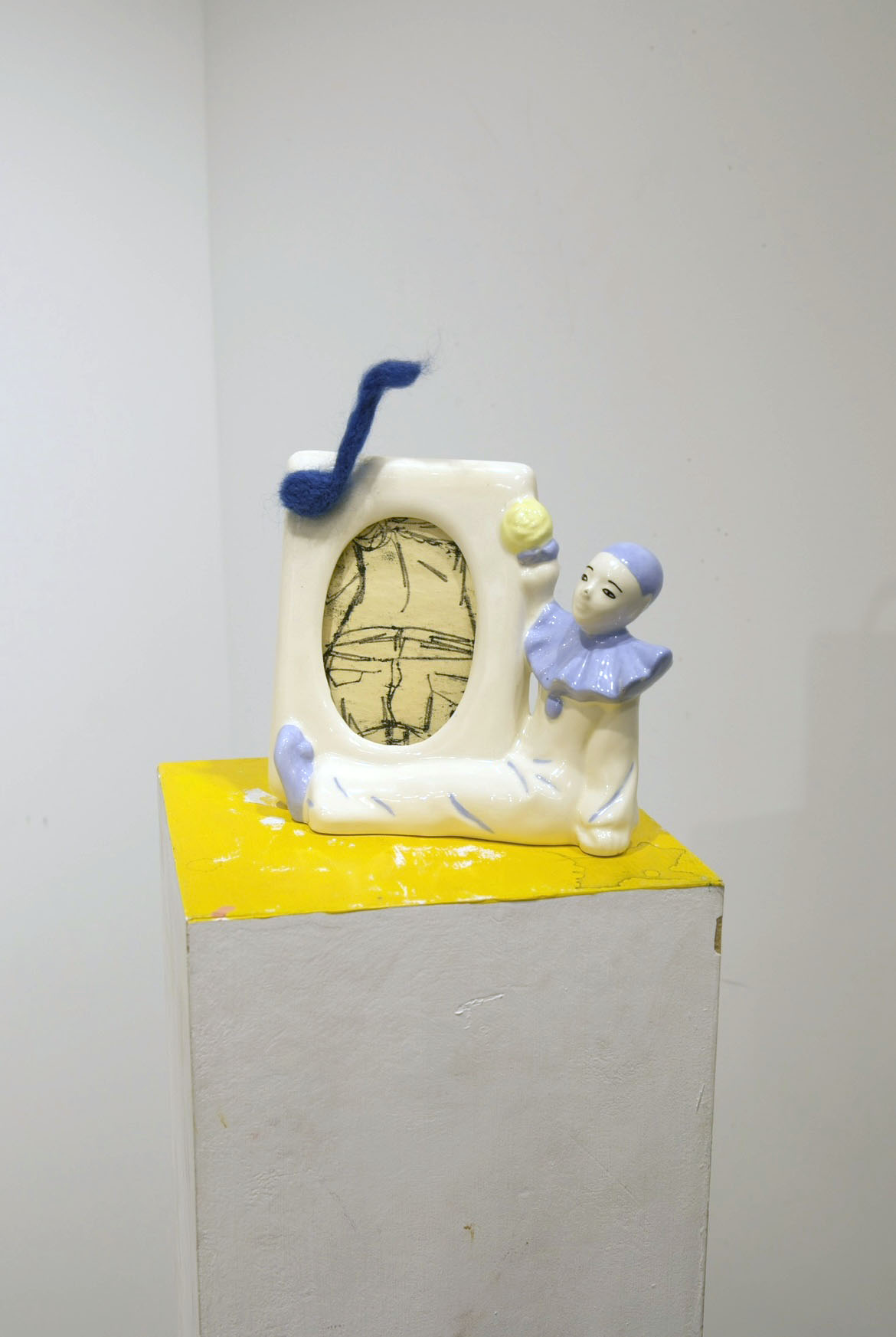

Similarly ruminating on her own interpersonal relationships, Victoria Sherwood is concerned with the lack of vulnerability and transparency in today’s fast-paced and media-dependent society. Although her multimedia works have wide-ranging materials like graphite, textile, and acrylic, she approaches them like drawings. Focusing on the meticulous and honest process of craftsmanship, she embraces trial and error despite an environment attuned towards automation and perfection. Sherwood relies on the honesty of creation by juxtaposing expectations of perfection and imperfection. Elements of media-fabricated images of beauty are reconstructed and recontextualized, encouraging a reassessment of how we interpret symbols in the face of today’s information explosion.

Paloma Brites plays with a different type of explosion: fire. Her work carefully treads the line between representation and abstraction, as she balances the dangerous and volatile nature of glasswork to create beautiful and organic forms. These works, usually measuring no larger than ten inches in either direction, are intimate vessels of sentimentality. It is through glass that Brites is able to be transparent with the viewer. The medium reveals not only her physical practice, but her psychic operations as well. The series of small glass sculptures in this exhibition are the product of the artists’ experimentation and exploration of her medium and herself. She values the time spent with her material, and it is through her work that Brites allows herself and her practice to be vulnerable.

Producing art during difficult times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, worldwide socio-political upheaval and an overall era of impermanence, the artists in “Object-Making as a Therapeutic Practice:” Susan Behrends Valenzuela, Rachel Graves, Victoria Sherwood, Paloma Brites and Briana Pierre all share experiences of discomfort, vulnerability, uncertainty and anxiety. This is manifested in their work but also relieved through the healing/therapeutic action of artistic production. In this online exhibition, we aim to highlight the technical and physical qualities of the works, whether it be a glasswork, a crocheted piece meant to mimic grass, the collaging of materials and stories, or a painting depicting family members. These artists’ practices allow them to translate intense emotions into physical works. Moreover, bringing these pieces into a virtual space adds yet another dimension of translation. As curators, we are interested in exploring the boundaries of our online platform by digitally transforming the traditional exhibition space, The Commons at Barney, into a living space. In their final year of their undergraduate programs, these artists are working in a transitory time and place. The internet has become a second home to many, especially during a time of global upheaval. In speaking to the artists about the nature of an online gallery, we have discussed the permanence of a digital entity such as this. This online exhibition functions as a form of documentation in itself, recording a moment in these artists’ careers, something that they can look back to and remember: a moment in their own personal histories. We hope that this digital space will continue to encourage and foster healing in both the visitors and the artists themselves.